We came across this interview from National Board of Review member, Thomas W. Campbell’s blog, with director Jim Szalapski. It’s an incredibly insightful look into the mastermind behind the masterpiece known as Heartworn Highways…

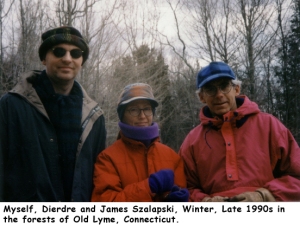

I met James almost 20 years after he made Heartworn Highways. He came into an edit studio I was working at to cut a trailer of an independent film he had shot. We became friends pretty quickly, finding that we were interested in the same kind of things – telling stories, wrestling with technology, UFOs and government conspiracies (which led us both the X Files). James was an accomplished cinematographer with one of the brightest and most inquisitive minds that I’ve ever met. He liked to problem-solve especially in story telling and the technical ways we communicate them. But James was also a pioneer who moved to New York City form Minnesota 10 years before I moved to New York City from Vermont (He was 10 years older than me). When he came to the city he found an empty and essentially forgotten PreSoHo (it was called by the name of the streets then) and moved into an incredible loft space on Spring Street, struggling through the default years and ultimately watching the region transform around him.

James was a pioneer who became a friend and mentor – he made a lasting impression on anybody who met him by being continuously supportive and always interested in what you were doing.

Whether shooting a documentary for PBS one month or directing a film with Roy Schneider later in the year James would always welcome the opportunity to actually tackle a new production problem – he was eternally ready to jump into life. Which made it all the more difficult for everyone when he finally passed away after and on and off battle with cancer that finally caught him in September of 2000.

Heartworn Highways is the great achievement in the life of someone who did a lot of pretty excellent things. It’s an honest and compelling look at a musical culture that was very much in transformation in 1976 – and was fortunately documented by James Szalapski and his small crew of merry filmmakers.

T. Campbell:

At the time the movie was shot, and right up until the time of its original release, the film was called ‘New Country’ but then something happened which made you look for a new title. Could you tell us about that?

J. Szalapski:

They came out with a yoghurt called ‘New Country’, right while we were cutting the movie and there was advertising everywhere … we don’t want people to think its a yoghurt movie, so we changed it to ‘Outlaw Country’ for a while because these guys where referred to mostly as “outlaws,” and tried to go for something more evocative, threw round a bunch of titles and this one came together like a feeling.

T. Campbell:

You mentioned that these guys were kind of, kind of outlaws and they broke off from Nashville… Can you give us some background on that?

J. Szalapski:

Well, by the early seventies Nashville had sort of become very rigid. All the songs were sounding the same, they just turned out product like crazy and they kept country music in a narrow defined range. But the young guys wanted to do something different. A lot of them had gone through the sixties and had experienced the whole explosion in rock and pop music and wanted open it up a little bit. “LA Freeway” is kind of an anthem for these guys; they went to places like LA and New York and, and discovered it wasn’t where they belonged. Their roots were in the South and they had an emotional connection to their grandparent’s generation there. But when they came back to Nashville and to Austin, Texas they brought back with them the electric guitars and the raw sound of their own generation. But the music they were making connected more to a generation older than the one in place in Nashville.

T. Campbell:

They looked to guys like Hank Williams …

J. Szalapski:

They where looking, back to them, and I found that very interesting, this generation jump which I tried to put in the film with some of the older characters in the film. Another thing that was happening was that there weren’t a lot of places to play music in Nashville – outside of recording studios. There were very few clubs there. But in Austin there was and Austin kinda became a new capital for this new music. Austin is a university town, very liberal, pretty advanced and there were a lot of clubs to play music in. It pretty quickly became like a rival to the main, established, “religion” there in Nashville.

T. Campbell:

I wanna get into how this film was made, but I’m curious that you talked about this group of people, these outlaws.

J. Szalapski:

My connection to all this was very personal and direct. The film is dedicated to Skinny Dennis. Dennis played stand-up bass around LA. And Guy Clark was in LA at that point, this was the late sixties. The movie opens with ‘”LA Freeway” which Guy wrote about LA and he mentions Skinny Dennis in the song, “Here’s to you ol’ Skinny Dennis…” Dennis rambled around and for a time came here to live with me in New York City in seventy-two or so. Guy had gone to Nashville so he went down to visit Guy, and suddenly he felt at home for the first time in his life. When he came back he told me about the scene there and I was at the point where I really wanted to make my own film and I thought maybe this could be an interesting subject. So I went down there and stayed with him and then just met the people that he knew, Guy and Townes Van Zandt. He dragged me over to see David Allan Coe who was kind of very different from them, more outrageous, you know. He’s like the biker. And Townes is the poet and Guy is like superb craftsman/writer …

T. Campbell:

…

He’s the one who repairs the guitar in Heartworn Highways?

J. Szalapski:

He also does that too, yes. Townes would be one of those people who wouldn’t do anything for a year and then sit down and write five songs in one night.

T. Campbell:

Dennis died before you made the film. Was there any forewarning of that?

J. Szalapski:

Well, Dennis had Marfan’s Syndrome. It’s a birth defect. Lincoln had it. And it causes your body to get very boney and elongate. Dennis was six foot seven and weighed 135 pounds that’s why they called him Skinny Dennis. The doctor said Dennis wasn’t gonna make it to his twenties, you know. And, he was a pretty hard partying guy, he didn’t walk around on tip-toes because of his heart problems. Eventually he did die of heart failure. He was twenty-nine. But back in the early seventies he introduced me to everybody in Nashville and Austin. I shot slides, I got copies of their music, most of the guys only had demo’s, they didn’t have albums at that stage. I took all that around and showed it to people to try to raise some money for the thing. And they said things like “Go and get Willie Nelson or Kris Kristofferson as a host for the film” and we’ll think about it, but nobody knows any of these people. But I wanted to go with the guys who were on the way up, I think they, they’ve got the most interesting energy, they’re the avant-garde on this thing that’s happening. So, finally, through George Carroll, I met Graham Leader in Paris who became the producer of the film. He was an art dealer in Europe.

The energy crisis had just hit and the bottom had fallen out of the art market. I played him the music and the music won him over. I also showed him some of my slides. So we went to Nashville and Graham financed what we felt was going to be an hour documentary for television. I think we had thirty-five thousand dollars. In about a month we had a small crew and were underway. We shot a couple of things the first day we were there, it was great, we were off to a running start, but then we didn’t do anything for four days. People’s schedules, cancellations, we just couldn’t get anything happening. The crew was getting grumpy… but then it took off. Way led to way and we started getting other people into it. I’d say it was about two weeks into it we felt we could make a feature film. So Graham he raised more money, basically over the phones and, and we finished shooting everything we could to make a feature. The whole thing took around four weeks.

T. Campbell:

How did the budget determine the style of the film-making?

J. Szalapski:

We went as lean as we could. Me and an assistant cameraman…My assistant cameraman on was also my assistant director, Phillip Schopper. We had worked together before and had become good friends. Phillip’s a very creative person with a lot of good and you want people around you who will keep you honest. Then when we got to the editing room he became the editor and I became his assistant editor. He was there at the Steenbeck doing all the cutting and I was finding stuff and looking over his shoulder.

And of course we would always confer about the editing with Graham Leader who stayed in New York for pretty much the whole course of the finishing the film. The grip was Mike Harris, Skinny Dennis’s best friend, who was then living in New York also. Larry Reibman was the gaffer. Larry was working for a film equipment rental house at the time and wanted to get out of the rental house and make movies. The sound man was very organic. He was great. Alvar Stugard was his name. Like I would walk into a situation and start looking around for how the light- ing falls and where the lamps are, what this is gonna look like. Alvar would walk around with his microphone and his headphones on, and test the acoustics of the room, and he would find the best sound might be over in the corner and he would say what sounds best for the place what really gives the feeling of place too, you know.

T. Campbell:

This is a technical question before we move on. What equipment did you use to shoot this film?

J. Szalapski:

A 16mm camera. About sixty per cent of the film was hand-held. I shot with an Eclair, French Eclair NPR, which is a difficult camera to use, it’s fairly heavy and the weight is about five inches in front of your chest, so you’re supporting it all with your hands.

T. Campbell:

Did you a use a Nagra stereo?

J. Szalapski:

Nagra stereo. We made a real effort to record everything in stereo.

T. Campbell: Really?

J. Szalapski:

And the final result was mag stripe stereo, 35mm film with mag stripe on the side. Because this film was done before optical stereo, you know, the whole Dolby optical stereo thing that came into movies happened about two years after we finished the film.

T. Campbell:

So not only the music’s in stereo but the presence, the dialogue track the chickens and the lambs and whatever are in stereo on the soundtrack?

J. Szalapski:

Right, and we tried to get it as high fidelity as possible but we only had two tracks so when someone was singing and playing a guitar we put one mic on the singer and one on the guitar. Then in the mix we would put their voice in the centre, where it is on the screen pretty much, but we’d spread the highs and lows out according to the position of the guitar. If the guitar neck is up to the right, you’d put the highs up there and put the lows down at the body and so we’d have a stereo separation for the scene.

T. Campbell:

Is all of the music performed live?

J. Szalapski:

Yeah. Oh, yeah. You know, people played music, like you and I are talk- ing then a couple of other people would drop over and somebody would say “I’ve got a new song”, and they try out their songs and sing together and so it goes. There was a lot of drinking, these things would go till three, four, five, six in the morning. Eventually people would sort of lose the ability to sing very well, you know, but they could still play. Their body seemed to remember the guitar stuff. I told them what I wanted to do and that I wanted to hear what they had to say about anything in this world, the movement, or whatever.

T. Campbell:

So what, what happened in a sense is that you meet one person, they would introduce you to someone else, they would introduce you to some- body else …

J. Szalapski:

Exactly. Dennis was friends with Townes and Guy they’re both very highly respected in the songwriting community. They’ve written a lot of songs, they’re very original. Once they were both interested in the film people said “Oh, you should go talk to so and so”. Since Guy and Townes were my main characters people would say “Oh well, we’re in. Count us in. You’ve got those guys, we’re in”.

T. Campbell:

Initially, you were asked to get Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson, right?

J. Szalapski:

Yes and actually once, when we were well into the project, we were in David Allan Coe’s hotel room and Willie Nelson was up stairs in the hotel. David said Willie would like to be in the film, just come on up, whatever you wanna do. It probably wasn’t economically the smartest thing but, I decided to stick to my original idea. I said thank you very much, but…

T. Campbell:

Were you a little wary that the direction might start to shift on the film, you might loose focus?

J. Szalapski:

Maybe lose the balance. I mean it would have been Willie Nelson and a bunch of these unheard of guys in this movie. I mean I love his music, I think he’s a great artist.

I could identify with these other guys more than him, and in a way I tried to keep it organic. I mean Dennis introduced me to these people, they introduced me to a group, and there were a couple of people that I discovered. Like Larry Jon Wilson. He was a chemist, a research chemist that just dropped out, and he’s always sort of been his own person. And Gamble Rogers who was the comedian. He’s such a wordsmith the way Guy Clark and Townes are. They’re kind of outlaws to the outlaw group almost, but I felt that there was the right feeling.

T. Campbell:

The film actually wasn’t just about these people as musicians but it was about them as people as well. And there’s a good example with Townes Van Zandt and the fellow who, I guess lives next door to him, the blacksmith. We see a little documentary glimpse into his life and then his relationship with Townes, And Townes does this really melancholy song.

J. Szalapski:

When we were travelling, when we flew to Dallas and stuff, flew to Austin, people would see us at the airport with all these cases of stuff and they would say “Are you guys a band?” and we’d say “Yeah, we’re called ‘Body Heat’”. (LAUGHS) It became the, the crew’s … (CHUCKLES) … nom-de- guerre, you know.

T. Campbell:

During the Big Mack sequence so much earlier in the film there’s this montage as well where you use, you use all these sepia tone photographs. Were they anyone specifically?

J. Szalapski:

A lot of ‘em were my father’s photographs. And there’s a scene, in fact, where he’s kissing my mother on the back of a Model A and there’s a big butterfly on the, on the back wheel. That was one of the things he painted, you know.

T. Campbell:

How long did the production take?

J. Szalapski:

We shot over Christmas and New Year’s holidays in Nashville and Austin. Everybody thought we were nuts shooting on the Holidays. But every- body was home and in a Christmas mood. And that’s why the movie ends with “Silent Night.” Charlie Daniels’ the big concert was done for his home college as a gift, that’s a college auditorium, and he put on the big full- out road show as he did in the big auditoriums…

T. Campbell:

At the time was he the one who was the most well-known nationally?

J. Szalapski:

Which is very emotional … you get the feeling it’s not just the words it’s the feeling, the emotion, it really overpowers him. We all tried to make a real effort to, to get to know these people before we stuck a camera in their face otherwise they couldn’t be that open. And that was moment’s really a gift, it’s a gift to the film because it gives an emotional depth that you can’t plan with a documentary, you can’t even hope to get that, that just comes if it happens.

T. Campbell:

Was Big Mack kind of a spokesman or a center of the film?

J. Szalapski:

He was sort of our anchor with the first generation. For the film, the way I felt, these musicians were anchored with that generation and the basis for their music. The Wigwam personified some of the feeling I had of this connection to our grandfathers. Big Mack was actually a gift from another friend, my friend George Carroll, with whom I’ve just finished writing a screenplay. George also introduced me to Graham Leader who produced the film and he was also good friends with Mike Harris and Skinny Dennis in California. He was driving to New York, he stopped in Nashville, saw a couple of the guys and ran across the Wigwam Tavern and Big Mack and the guys in there. He says “You’ve gotta meet this guy, you’ve gotta shoot this thing.” George had a ’66 Pontiac Grand Prix, two door but it had a huge trunk and that became our production vehicle. We put the whole crew in the Pontiac and filled the trunk full of camera equipment and drove around Nashville. I remember the heater didn’t work and it was Christmas and New Year’s Nashville gets cold, but we had so many people in the car that body heat kept us warm. Periodically

J. Szalapski:

Yeah. In fact, shortly after “Heartworn Highways” was made “Urban Cowboy” came out with John Travolta, James Bridges directed. And he used Charlie Daniels doing the same song “Texas.”

T. Campbell: And post-production?

J. Szalapski:

That took from the middle of January to the spring. Four or five months, something like that. We’d actually screened it for the guys that were doing Filmex, the big LA festival. They said, “We think it’s the best docu- mentary we’ve seen since Woodstock and we wanna open the festival with it and make you the big cause celeb, we discovered you, blah, blah”. But we could not get the film ready in time for the press screenings. We did get it ready in time for the festival and we ran just as another film, but we needed it before that to screen to get all the advance press. The lead film just had to be that right, and we couldn’t do it. Graham and I also showed the film to the studios to see if we could get a studio interested in distributing it … we were encouraged to death but nothing happened. We went into 20th Century Fox, we had some meeting with a big producer, who had ‘Close Encounters’ on his desk which they were thinking of doing. Graham and I sat in on a screening of “Heartworn Highways” with him, you know. And he looked at ten minutes and he told the projec- tionist to stop. He said “This is a great movie, I gotta get some other people down here, you know”. And started bringing in the marketing people.

They had like four or five screenings for it. And everybody said “We don’t know how to sell this, this is seventy-six, I don’t think the coun- try music market’s a very big market. I think we’ll pass,” and that was sort of the way it went. Until, through a friend of a friend again, we met James McManus who was running a prosperous marketing company in Connecticut. He was interested in films and really liked the film and bought the US rights for it and opened it … I feel like in some ways the film’s been dogged by a lot of bad luck. I mean we had our New York premiere, and the first weekend was Memorial Day. (CHUCKLES) So everybody left town. And the second week we had horrible rainstorms, so very few people showed up. And it’s the kind of film that if you don’t get some people talking about it, you know, it’s … and there wasn’t a lot of money to do any big advertising push. But around that time there was something called the Independent Feature Project which put a package of films that toured around. They picked up Heartworn and it went around the country with that. Playing mainly the art theatres, which we don’t really have anymore but were fairly prevalent then. And Graham was able to sell it to Channel Four in England, sold it to Germany, you know, Ireland…

T. Campbell:

At that time … seventy-six?

J. Szalapski:

This would have been the late seventies now. All these things took a few years for them to work out. We sold it on television where we could, but nobody ever has bought it in the United States for television.

T. Campbell:

The opening sequence with Larry Jon Wilson… let’s talk about that. How did that sequence come together?

J. Szalapski:

I loved the song, the song was something from one of his albums that I’d heard. And he was in the recording studio working on an album, so I said “Okay, let’s shoot how a song’s put together for an album”. Larry Jon was willing to do that song, so … And we found a couple of musicians to play and some he knew, but he wasn’t from Nashville so these were just pick up guys, and studio guys came round, so he had to kind of teach ‘em the song, you see some of that, and inspire. One of the guys wanted to do the overdub because he was a good harp player and so Larry Jon sort of directed him and that was the song. Larry Jon’s voice has such a wonderful gravelly quality. And there’s and interesting moment when there’s a little break in the studio thing, so … Larry Jon starts playing and he’s playing a Lightning Hopkins blues riff, and then they both kinda play along and then the bass jumps in and he does this little piece of Hopkins which shows the source of Larry Jon’s influences, you know, going back to the first generation of country, blues, country western …

T. Campbell:

So I want to ask you about documentary film-making, maybe specifically, um, how, how have your feelings towards documentary film-making changed since making the film and how did making the film itself define your feelings about documentary filming?

J. Szalapski:

I was an artist. When I went to college I studied both journalism and fine art. And I got fascinated with photography because my father had done a certain amount of photography and that became my main fine art lean- ing. When I got out of college I had the opportunity with documentary to combine the two things, journalism and photography, which some people argue is not fine art. I ended up in New York, and first started just getting some work on crews for commercials and so on. I Used my fine art background to design sets and then I moved into doing some gaffing and lighting, then I became an assistant cameraman, moving toward shooting some of my own stuff on super 8 film … I started working for French TV, help out with the lighting for French TV’s little three man crews. They helped me a lot. French TV were amazing … They’d go out with two people. The cameraman would bring a couple of six-fifty (quartz) lights and a soundman and then they’d have a producer from television. And they’d go make hour documentaries on 16mm, and they’re beautiful things.

T. Campbell:

That was kind of a training ground for you?

J. Szalapski:

Yeah. I learned how to work very simply and with very little equipment, get a lot out of it, be sensitive to what’s really there. They only had a couple of days, on these things and I had to get people to trust you and open up to the camera quickly. We did hour documentaries on like Howard Hughes and William Randolph Hearst, “The Untouchables”, all these great American icon things. And learned a lot from the French about getting the great stuff without a lot of fuss and minimal crew and being very inventive. How to find the good restaurants in town. (LAUGHS) These guys… by the time we were out of the airport usually they had the names of two or three great restaurants no matter what little town you were in, Iowa orKansas. And then, I worked on this feature length documentary, an independent film. I went from being an assistant cameraman to working as the assistant editor. So I sat down to start editing, and I had sixty thousand feet of film that was shot for this documentary over the course of about four years, and it was total overload. I mean working for this guy who was super precise. I mean he would say things like take a frame off the outgoing and add two frames to the incoming shot, which in 16mm is no small feat. You have to put a piece of tape on each frame and write the edge numbers so you can put it back where it goes eventually if need be. It was a traumatic experience. I mean, I would edit all night in my sleep and come to work the next day, working twelve, four- teen hours a day. But I learned a lot about editing, what you can do in editing. It’s a major part of film-making, especially documentaries. And that’s how I got into making documentaries.

T. Campbell:

Since ‘Heartworn Highways’ … I’d like to talk a little bit about your experience as a cinematographer and what’s involved.

J. Szalapski:

Yeah. Things have gotten very varied. I’ve always been technically orientated. I was a hot rodder in high schoolbuilt, souped up cars and things. My father a sign painter for the railroad, painted all the emblems on the trains and taught me how to letter and pin-stripe and all that. So as a teenager I went into painting race cars to flame jobs on hot rods and lettering and drag racing, that was my part-time job in high school and college.

T. Campbell: Where was this?

J. Szalapski:

In Minnesota where I grew up. I got into the airbrush because of this and started doing the sweatshirts with the caricatures of cars and monsters and all that stuff. And we would do car shows and fairs, state fairs and work my way totally through college and high school, doing that stuff. So after “Heartworn” I had the opportunity to start doing some special effects things, and hooked up with a place here in New York R Greenberg Associates, and it was two brothers, Robert and Richard Greenberg. They had just done the titles for “Superman” which got them recognition in the industry. And we started shooting trailers for features. We did the trailer for “Alien”. They were trailers but they were metaphors for the movie. They weren’t scenes from the movie, they were some other construct. For the alien who built the egg, that cracks open on this parched landscape and light shoots out. In fact, in that little tiny oven over there we made all the parched earth for the egg to sit on in the moonlit landscape in the ‘”Alien” trailer. We did “All That Jazz”, built the sign for ‘All That Jazz’, all the light-bulbs here in the loft, and I worked out the programming so that it, you know, these little sequence switches so it animated. The trailer we did for “All That Jazz” with the sign became the opening titles of the movie. Bob Fosse saw it and said, “This is beautiful. Let’s start the movie with this,” you know. And there’s that whole, like, rehearsal scene that’s even cut with shots of the sign. We did a block ice with something moving inside of it that explodes in front of you and then the title “The Thing”, John Carpenter’s “The Thing”.

I shot the, the opening to “Garp” with the baby flying through the air, with George Roy Hill. And we did a number of movies like … “American Werewolf In London”, a lot of trailer things were in title sequences for movies and were quite innovative and very controlled, you know, this was all before motion control, all the opticals were done as film opticals, there was no digital. Then periodically documentary-type projects would come up. Greenberg started doing more commercials, special effects became more a part of commercials. Mid-eighties I wanted to direct commercials, so I started a company with a couple of people and for three or four years that company existed. Then it fell apart, and I continue to direct commercials, documentaries and apply what I learned from Greenberg to other things like industrial films.

T. Campbell:

What would you have done differently on this film if you were to do it again?

J. Szalapski:

I don’t know. I wanted to capture a kind of movement, a kind of a revo- lution — to do a portrait of that rather than of three guys. I felt there was a change happening to country music, a sub-culture within in that was becoming powerful that would affect the main culture. So that’s what I went after and that’s why I, I felt like I needed to cover a lot of different areas from the established star like Charlie Daniels to the struggling singer/songwriter to David Allan Coe who’s … even an outlaw amongst the outlaws.

T. Campbell:

Do you still listen to country music?

J. Szalapski:

Yes. I have very varied tastes on music. I mean, I listen to a lot of clas- sical, jazz. I mean I was … a big fan of Miles Davis. I listen to the guys that I did the movie with, I’m always interested in what they’re doing … In a lot of ways it’s…

T. Campbell:

What’s your feeling about the audience right now and about what’s going on in culture and how, how does this film fit in, how do these guys fit in twenty years later?

J. Szalapski:

Well they’re basically still doing what they were doing then, they’re a little older but they’re still writing and singing songs about life as they see it. I have to say, I think they’ve all been very true to their, er, to their original style of music and their original goals.

External link: http://twcampbell.net/2012/01/16/james-szalapski-film-maker-interview/

LOG IN / Register

Thanks for visiting the new home of Heartworn Highways! Here you'll soon find loads of bonus content from both the original and new film, AND in the coming months, both feature films for your viewing pleasure. Please join our community so we can keep you posted on events and new content as it becomes available. Click here to register. Thanks again!

Join with social